Estimated reading time: 9 minutes

Shelling is more than a walk along the shore—it’s a quiet exploration of coastal ecology. It often begins with the simple discovery of a seashell. For beach homeowners and frequenters of coastal regions, collecting seashells provides a tangible connection to the ocean. It is also a way to observe local marine life. Among the shells that commonly wash up are two primary types: bivalves and gastropods. Bivalves, such as clams and scallops, consist of two hinged shells. These typically come from mollusks that burrow into sand or mud. Gastropods, including snails and whelks, have a single coiled shell. They often live on or near the seafloor. While they may seem similar at a glance, these two categories reflect different life forms. They also have different behaviors and habitats.

A Note on Ethical Shelling: Leave Live Shells Behind

While the thrill of discovery is part of the draw, responsible shelling is essential to preserving marine ecosystems. Many coastal states, including Florida and parts of the Pacific Coast, discourage or legally prohibit the collection of live shells—those with the living organism still inside. Each seashell taken disrupts natural food chains and depletes local populations. It can also impact water quality. Even shells that appear abandoned may still host living animals such as hermit crabs. As a general rule, if a shell is occupied or shows any sign of life, leave it in place. For those who live near or frequently visit coastal regions, modeling good shelling etiquette helps protect the very beauty that draws us back to the shore. This happens season after season.

The types of shells you find vary significantly depending on the region. They range from the craggy shores of the Pacific Northwest to the sandy Gulf Coast. Knowing how to distinguish them elevates every walk by the water. Here are ten of the most common and recognizable seashells you might encounter across U.S. beaches. Their coastal locations, shell type, and defining characteristics are also included. Happy shelling!

Atlantic Bay Scallop – Upper East & Mid-Atlantic Coasts (Bivalve)

The Atlantic Bay Scallop (Argopecten irradians) is a classic bivalve, with its distinctive fan shape and ridged symmetry. This species lives buried just beneath sandy beds. It is known for its rows of small, blue eyes along the edge of its soft body. Empty scallop shells often wash up along the beaches of Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and coastal New Jersey. Their colors range from pale white to rusty orange or pink. Their ridges catch the light in tide-scattered clusters, especially after storms.

Slipper Shell – Upper East, Mid-Atlantic, & Pacific Northwest (Gastropod)

Though its structure appears bivalve-like at first glance, the Slipper Shell (Crepidula fornicata) is a gastropod. Its domed, boat-like top and internal shelf are the clues. It attaches to rocks, oyster shells, or even other slipper shells. They often form stacks of multiple individuals. Found from Maine to the Carolinas and again in the Pacific Northwest, these seashells are usually gray or cream-colored. They may be encrusted with algae or barnacles, reflecting their often-stationary lifestyle.

Coquina Shell – Southeast & Florida Coasts (Bivalve)

Small, smooth, and often vividly patterned, Coquina Shells (Donax variabilis) are colorful bivalves native to warm Atlantic and Gulf beaches. From the Carolinas down to South Florida, especially on Sanibel and Daytona Beaches, they appear in purples, yellows, and stripes. They are often scattered in the wash zone. When alive, coquinas actively burrow back into wet sand as waves retreat. Their discarded shells often litter the shoreline in great numbers.

Lightning Whelk – Gulf Coast & Florida Panhandle (Gastropod)

The Lightning Whelk (Busycon perversum) is a striking gastropod known for its large, spiraling shape and left-handed coil—a rare trait among whelks. Found primarily along Texas and Louisiana shores and throughout the Florida Panhandle, these shells are heavy and ridged. They can sometimes be more than a foot long. Their creamy tones with storm-gray stripes resemble bolts of lightning. These are often prized by collectors for their dramatic form and durability.

Moon Snail – Mid-Atlantic, Florida Gulf, & Pacific Northwest (Gastropod)

The Moon Snail (Neverita duplicata on the East Coast; Euspira lewisii in the Pacific Northwest) is a thick, globular gastropod with a smooth spiral and pearly interior. These snails are carnivorous and bore neat, circular holes into bivalves. Thus, a shell with a perfect hole may have fallen victim to one. They’re commonly found from New Jersey to the Gulf Coast and across Oregon and Washington, often in sandy flats after low tide.

Olive Shell – Southeast & Florida Atlantic Coast (Gastropod)

The Lettered Olive (Oliva sayana), a glossy and tightly coiled gastropod, thrives in the intertidal zones of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida’s Atlantic beaches. Named for its brown hieroglyphic-like markings—like cursive letters—it has a smooth, cylindrical shape and a shiny finish. The gloss is thanks to its mucus-secreting mantle that polishes its shell. Often found burrowed just beneath the sand, the Olive Shell is a favorite for its lustrous appearance and uniform shape.

Pacific Sand Dollar – California & Pacific Northwest (Bivalve Relative / Echinoderm)

Though technically not a shell-forming mollusk, the Pacific Sand Dollar (Dendraster excentricus) is a close relative of sea urchins. It deserves inclusion for its prominence along the West Coast. Found from Southern California to British Columbia, it has a flat, disk-shaped skeleton called a “test”. It features a five-petal pattern on its surface. When alive, it’s covered in tiny spines. After washing ashore and bleaching in the sun, it takes on a smooth white appearance. It becomes fragile yet highly recognizable.

Jingle Shell – Upper East, Mid-Atlantic, & Southeast (Bivalve)

The Jingle Shell (Anomia simplex) is a delicate, translucent bivalve that often adheres to rocks and oyster reefs. Found from New England down to Florida, these thin shells range in color from gold to silver to bronze. They make a soft, musical sound when collected in quantity—hence the name. Their asymmetrical, almost paper-like structure sets them apart from more robust bivalves. These shells often gather near mussel beds and rocky shores.

Auger Shell – Florida, Gulf Coast, & Southeast (Gastropod)

Long and tightly spiraled like a drill bit, Auger Shells (family Terebridae) are slender gastropods common along Florida’s Gulf Coast and Southeastern beaches. These tan or cream-colored shells have numerous whorls and sharply pointed tips. Augers often inhabit warm sandy shallows. They are active burrowers, making their presence more obvious after storms. They’re often unearthed and scattered across the shore.

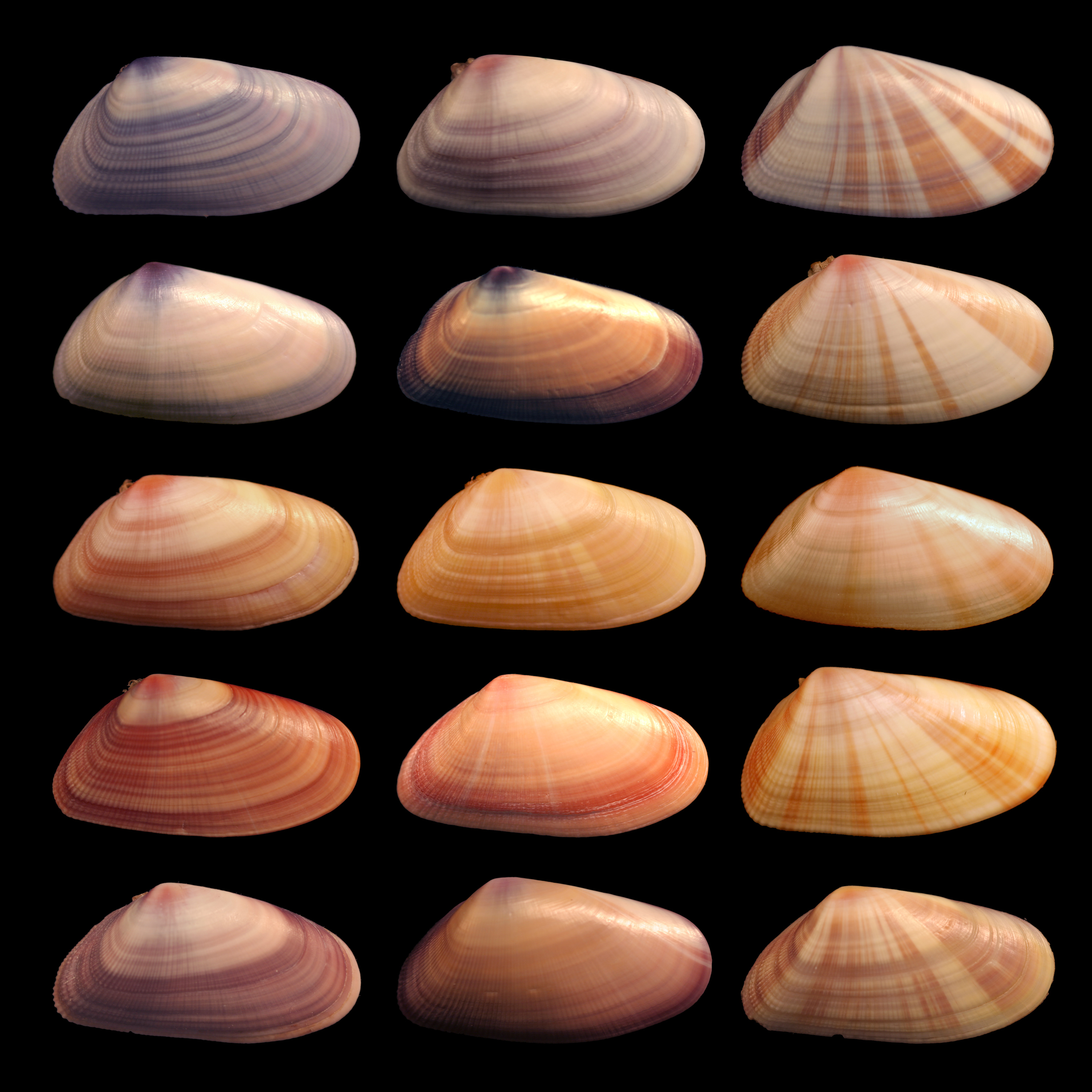

Cockle Shell – California, Gulf Coast, & Mid-Atlantic (Bivalve)

Cockle Shells (family Cardiidae) are large, ridged bivalves with a rounded, heart-shaped appearance. Common along the Gulf Coast, Mid-Atlantic shores, and parts of California, these sturdy shells come in shades of white, coral, or brown and are known for their deep radial ribs. They’re often found whole and are among the easiest to spot due to their size and symmetry, especially on beaches with coarse sand or after high tides.

Each shell tells a quiet story of marine life, current patterns, and coastal conditions. For beach homeowners and enthusiasts, identifying whether a find is a bivalve or a gastropod adds an extra layer of meaning to the collection. Shelling with this deeper understanding transforms the experience from casual scavenging to coastal interpretation—one that’s regional, seasonal, and rich with ecological context. For more beach-inspired activities, visit Beach Homes Lifestyles.